Noah Brehmer

Noah Brehmer is a theorist, editor, and organizer “from here” in a city that variously goes by Vilna, Vilne, and Vilnius. Together with friends he contributes to the circulation of autonomous forms. Recent works include: As if this World No Longer Existed: Three Theses on the Crisis of Political Belonging (ed. Neda Genova, Institute for Network Cultures, 2025); “We Do Not Belong Here: From the Diaspora to Jalūt” (Der Spekter, 2025); “A Nomos of the Stateless” (Blind Field Journal, 2024); “The Living Communism of Friendship” (Contradictions Journal, 2023). Brehmer is the editor of Paths to Autonomy (2022, Minor Compositions), and the co-editor of The Commonist Horizon (2023, Common Notions), and the ULWC Reader (2021, Luna6).

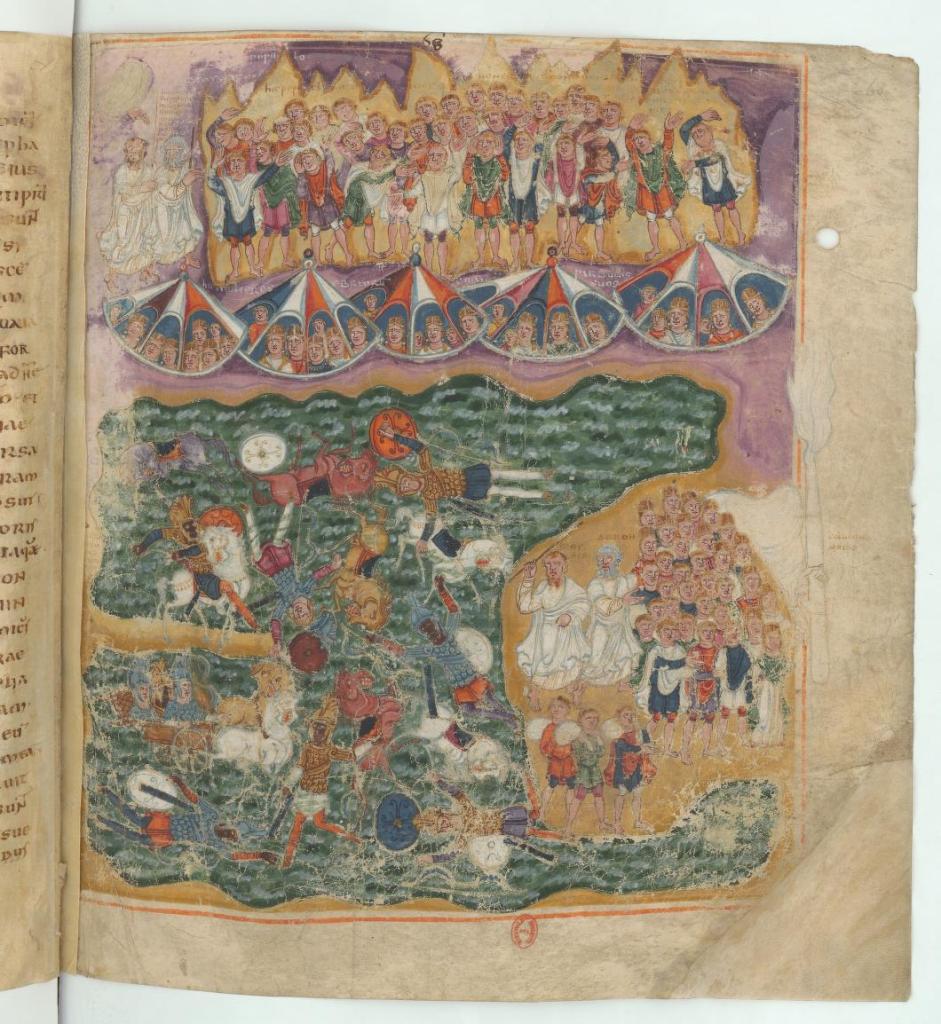

At the end of the second millennium B.C., what we may call the Middle East today was going through a sequence of upheavals that uncannily rhyme with those of our present moment. The rapid emergence of amorphous masses of ghurba (what we may call refuges today) lacerated the territorial integrity of Assyrian, Babylonian, and Egyptian providences. The catastrophic Minoan volcanic eruption on the island of Thera in 1600 BCE fomented apocalyptic ecological disturbances – the landscape was devastated by floods and then invasions, wars, and resulting mass displacements. The Hittite, amongst other former dwellers of nomoi (sg. nomos)[1] – having fled down through the geography of Lebanon as their providence collapsed from the North – found themselves exposed to a vertiginous social landscape that served to radically unground former political subjectivities.

Threatened by this ungrounding zone of non-being, the inchoate multitude were left with several options. Some, understandably, searched for a reclamation of their sedentary political communities, through ad hoc establishments of new tribal orders that were mythologically proclaimed in the aftermaths of sieges on settlements; while others, brought to their knees like exhausted animals, found themselves bartering their own skins for bread and seed.

And finally, there were those, having neither re-established themselves as subjects of a nomos through conquest, nor followed in the fate of the subjugated, were pushed out into the “desert wilderness.”

It was within the merciless desert, a zone of nonsubjugated exclusion from the nomoi of the earth, that a new form of political community emerged. A motley assortment of wanderers, outlaws, and robbers came to be called, by the citizens of Arkadian city-states, the khabiru—the vagrants. “And khabiru softened in the desert air, becomes Hebrew.”[2]

And while the Hebrews, as canonical history will assure us, grew ever distant from their vagrant origins – founding the Israelite Theocracies of the 2nd(BC) and now 3rd(AC) millenniums – the khabiru, the community of others, was never truly purged. Not even the final solution, attempted by the Nazis and carried by the Zionists today – i.e. the eradication of exilic Jewish being and exilic being generally – served to accomplish this task.

Today, the khabiru is the title of anyone who pledges to no nomos, who enlists themselves as the internal exiles of the city, who sees themselves in otherness, in the alien, in any form of life that resists, that persists, that refuses to belong to the world-annihilating home of humanity offered and imposed by empire.

In what follows, you will find an initial study of the 2nd millennium khabiru. I will explore the exilic politics of vagrancy and its repression through the Hebrew-Israelite political mythology of exodus. Carefully dissecting the Mosaic technology of exodus – conceived in general terms as an organized secession from the spatio-temporal ordinance of a nomos – I will introduce limits and even contradictions inherent to this political strategy. Rather than approaching the khabiru as a community founded in exodus, I will conclude by saying that it is more useful, for efforts to recover the abjected genealogy of vagrancy in question, to consider khabiren practices of belonging through a bond characterized by obstinate incompletion. The dialectics of exile, I suggest, offers itself as an articulation of vagrancy’s inarticulations.

Exodus

In the Theological-Political Treatise, Spinoza narrates the degeneration of the radically communistic form of life established by our khabiru, following their alleged exodus from Egypt, into theocratic, monarchic and finally tyrannical orders, of the twelve tribes. Let us consider the nature of this degeneration and ask: does the founding myth of exodus, despite its seemingly antithetical relation to the preceding forms, hold in some inherent sense their contents?

In Spinoza’s account, after flight from the Egyptian nomos, the Hebrews found themselves in the desert. Here they were both exposed to the harsh realities of a barren ecology and in a topology outside the desert of slavery – i.e. of their destitute existence as the oppressed and exploited partial-beings of the city-state.

Having just abolished their subjugation as slaves, Spinoza recounts, the liberated Hebrews would put themselves at the mercy of no man. Yet, as Spinoza will be sure to note, having lived the life of a slave, they in no sense held any inherent capacity or knowledge for self-rule. It is at the cross-roads of these two states – a state of liberation and state of destitution – that our vagrants encounter God.

However, it is not Moses alone, as the canonical story tells us, who is offered access to the metaphysical plane. As Spinoza stressed, “the right to consult God, receive laws, and interpret them remained equal for all, and all equally without exception retained the whole administration of the state.”[3]

For the desert vagrants, what Spinoza refers to as a state could hence be more accurately described as an oath to metaphysical statelessness. Divine right was shared by all as the living deeds and spoken words of a social contract with an interplanetary power. And it must be emphasized that this covenant between the vagrants and god was mediated by the terrestrial plane – the desert. In other words, it was not as though metaphysical statelessness was simply without place. As Julian Jaynes aptly observes: “In the times of Moses, that is before the conquest of Canaan, all metaphysical events take place in the desert, and therefore, as soon as he wants to speak with IHWH, Moses must […] leave the city, that is the sphere of power of the Egyptian Elohim.”[4] The desert, as a topological outside of the nomos, or as Spinoza will at times refer to as “wilderness” or “nature,” is a terrestrial interlocutor between the finite and infinite plane. Metaphysical, interplanetary, statelessness wasn’t simply an ideal up in the heavens but a “praxis needed for survival in order to uphold a certain kind of collective existence” beyond the nomos of the earth.[5] The khabiru’s covenant with the cosmos was thus terrestrially mediated through the desert’s otherness, it was not a final and “full” territory, but the ingression of an “elsewhere” in the here and now.[6]

Yet, as Spinoza quickly points out (in the same paragraph), the vagrants “were terrified and astonished when they heard God speaking,” and “gripped by terror,” they approached Moses, the leader of the exodus, and said: “Behold we have heard God speaking in the fire, and there is no reason why we should wish to die. This great fire will surely consume us. If we must again hear the voice of God, we shall surely die. You approach therefore, and hear all the words of our God, and you” (not God) “will speak to us. We shall revere everything God tells you, and will carry it out.”[7]

Accepting his appointment as the sole maker and interpreter of divine law, the first covenant was henceforth abolished. And with its abolition of law came the steady transformation of the living gestures and shared virtues of the interplanetary community of vagrants, into the terrestrial doctrines of an emerging nomos of the earth.

While the second covenant was enshrined in a stone tablet by the hand of the infinite plane itself, the third covenant, appearing in the aftermath of Moses’ destruction of the interplanetary covenant in retaliation for idol worship (the Golden Calf), was written by Moses himself, now only under the guidance of divine right. It is at this point that we see the full transfiguration of the cosmic plane into terrestrial rule. The genocidal conquest of the Canaanites, the partitioning of the land into a territory of twelve equal parts, and establishment of the Levites as the ruling sect of the High Temple, would all follow in turn. We have now arrived at the historical scene where the Israelite theocracy of the second millennium was born.

Notably, in Spinoza’s account of the degeneration of the interplanetary covenant into theocracy, then monarchy, and from there the tyranny of kings, civil war, and the collapse and conquest of the Israelite nomos by the Roman Empire – a critical detail must be stressed. The vagrants of the first covenant – now entirely stripped of their divinity as the so-called worshipers of the Golden Calf – did not voluntarily transfer their divine birth right to Moses and the ruling Levite elite, without a surmountable resistance.

The story of this stronghold of heretical vagrant partisans, who came to be known variously as the Sons of Nabiim, the prophets of Baal, the followers of Korah etc., sporadically appear throughout the Old Testament as “glimpses of a strange other world.”[8] For the Judaic-Israelite nomos this persistence of an “elsewhere” was understandably perceived as a critical existential threat to the theocracies’ efforts to negate exile and fully establish terrestrial rule.

And so the desert vagrants, as Spinoza recounts, began to resent Moses and question the infallibility of his claims to divine command.[9] In one such episode, a commotion spread throughout the tribes, who implored Moses to deliver his promises of redemption upon which their present slavery was assured: “[…] you haven’t brought us into a land flowing with milk and honey or given us an inheritance of fields and vineyards. Do you want to deceive these men; Hebrew will you gouge out the eyes of these men? No, we will not come!”[10]

Unwilling to deliver redemption in the here and now, Moses and the emerging Israelite elite were unable in turn to pacify the escalating protest. And so, as gruesomely recounted in Numbers 16, Moses called upon God to annihilate them all – and so it followed: “They went down alive into the realm of the dead, with everything they owned; the earth closed over them, and they perished and were gone from the community.”[11]

The emergence of the Ecclesiastes, with their rational study of law – dictated by the written word, inscribed on the tablet and the page – was advanced by the Israelites as an epistemological counterpart of this imperative to cleanse the chosen people, via annihilation, of the detractors.[12] Against the khabiru’s interplanetary law of the heart and living deed, Ecclesiastes labored to separate truth from the subject and enshrine it in the guarded walls of the high temples.

And while the exilic right of divine non-belonging persisted as an inextinguishable movement throughout the exodus and post-exodus eras – “From time to time,” as Jayne notes, “they were hunted down and exterminated like unwanted animals.”[13]

I will remove both the prophets and the spirit of impurity from the land. And if anyone still prophesies, their father and mother, to whom they were born, will say to them, ‘You must die, because you have told lies in the Lord’s name.’ Then their own parents will stab the one who prophesies.[14]

Post-Exodus

In the Israelite theocracy, there was no greater punishment than exile, for the worship of God “could be practiced, all agreed, only on their native soil, as it was held to be the only holy land, all others being unclean and polluted,” and for this reason, as Spinoza follows, “no citizen was condemned to exile: for a transgressor deserves punishment [and this includes death] but not disgrace.”[15] The postulation of a redeemed, “full existence,” that was established in the aftermath of the era of exilic vagrancy, hence foregrounded a “radical demand for total self-obligation to the collective” – as Raz-Krakotzkin observes about the theocracy of the third millennium.[16]

This injunction toward total self-obligation to the kingdom foregrounded a politics of sacrifice that placed the suffering and death of the individual categorically under the nomos. Such a post-exilic politics of sacrifice resonates with what Nancy conceptualized as a politics of communion. Derived from the Christian formulation of community as the absolute fusion of the individual into the collective body of Christ, Nancy concludes that its completion necessarily implies an absolute sacrifice of otherness, which is in the final instance a suicidal sacrifice of the self: “Thus the logic of Nazi Germany was not only that of the extermination of the other, of the subhuman deemed exterior to the communion of blood and soil, but also, effectively the logic of sacrifice aimed at all those in the “Aryan” community who did not satisfy the criteria of pure immanence, so much so that—it being obviously impossible to set a limit on such criteria—the suicide of the German nation itself might have represented a plausible extrapolation of the process [.]”[17]

Post-exodus politics is thus the negation and repression of exilic life – of otherness, negativity, groundlessness, and vagrancy.

It was no coincidence that Hannah Arendt saw the deterioration of asylum rights during the interwar period as the first major damage to the legal foundations of the nation state’s “human rights.” Exile – quid est in territorio est de territorio – with its “long and sacred history dating back to the very beginnings of regulated political life” was rendered inconsequential by the system of extradition treaties established by the League of Nations.[18] The negation of exile exposes humanity to an unmediated relation to sovereignty. The negation of exile, as Arendt bitterly continues, makes the loss of home and political status fully identical with expulsion from humanity.[19]

The Community of Others

I would like to suggest that Spinoza’s study of exodus could be approached as a cautionary guide for contemporary liberation movements – movements tasked today with battling the kings and masters of theocracies, plutocracies, monarchies, and sovereignties. Foremost, it raises the question of how to circumnavigate the ever-present temptation – and, concretely spoken, coercion – of the liberated to surrender their interplanetary statelessness to the physiognomical security and assurances of the city-state’s walls: those so called guarantors of the mortal actors’ continuity through time.[20]

In contrast to the politics of exile as a practice of bearing one’s own partiality in relation to the communities and territories one inhabits, exodus has a certain propensity toward the promise of a full existence elsewhere. Exodus operationalizes the exilic, it turns partiality into a means for another end. The question we must ask is: where is this elsewhere, this “wild” or “natural” outside, that the liberated use as a means to reconstitute themselves as full beings? Are deserts, forests, maroons, and mountains, really zones of “autonomous nature”?[21] Or, as Malcom Ferdinand has astutely observed, are they rather abject ontological domains; topographies and epistemologies unavowed by the colonial order?[22]

We must ask ourselves the following question: Is it possible to imagine exodus without a frontier – without a projected, a fantasized, “outside” that is used as means, as a sacrifice – in order to achieve communion? For instance, while Mårten Björk’s study of the Goldberg Circle offers a tantalizing framework for strategizing a politics of exodus, the idea of “living outside the ‘field of activities’ of capital” or of “overcoming of capitalism through migration” brings him to the uncritical presentation of the phalansteries in the United States and kibbutzim in Palestine as “ways to live outside the confines of the industrial system of capitalism.”[23] Marx, himself, saw the “free proprietors” of the American frontiers as a “direct anthesis” to the capitalist mode of production, but he was unable to recognize on what land and to whom this free proprietorship was given its conditions of possibility.[24] Martin Buber followed in Marx’s oversight in the early 20th century when he argued that European Utopian Socialism was better suited for an empty land, like Palestine. In Paths in Utopia, Buber encouraged European Jewry to flee the apocalyptic contradictions of modernity by joining a spiritual exodus to the free land where they could build socialism unencumbered by the impediments of capital, private property, and the sovereign state.

Paolo Virno and other key protagonists of Italian post-autonomist thought are the inheritors of this genealogy of exodic politics and its seeming dependency on colonial erasure today. While Virno carries Marx’s thesis point blank into the present, blindly fetishizing American frontier autonomy and applying it onto the flight of cognitive labor from the factory system of the 70s; Hardt and Negri attend to the problem of indignity and black social death in Empire, only to better safeguard their concept of “networked republicanism,” which they turn to as an exodic transformation of European sovereign power into a deterritorialized constituent multitude of free proprietors of labor.

If the exodic temptation to use otherness – whether of spaces or of subjects[25] – is clearly fraught, what would it entail to formulate a practice of the political beyond and against the entropic physis cult of today’s capitalocene? What, in other words, would a non-denialist politics of flight entail?

Returning to Ferdinand’s critique of Malm’s fetishism of the wilderness, we can begin by retreating a politics of the outside by seeing it as relationally bound to the inside. Rather than a nonplace to become again, the “outside” should be avowed as bearing its own inherent and incommensurable temporalities, agencies, languages, and knowledges.

It is at this critical juncture that the dialectics of exile feels pertinent. I see the concept as a contribution to a constellation of strategies and technologies for a non-denialist politics of flight from the here and now, within the here and now. As I have elsewhere developed, exilic belonging unfolds on a dialectical threshold between the inside and the outside. The stranger, khabiru, ghurba, or exile mark the entrance of the outside in our very midst: a dialectical folding of our interiorities into exteriorities and our exteriorities into interiorities. The outcome of this folding is thus established through no social bond “unhappily superimposed upon ‘subjects” but rather through the unmaking of them – through what Nancy has called the practice of sharing: my incompletion before the other and the incompletion of others before me.[26]

Returning to the topology of the desert and the khabiru, we could retreat their relation as no longer an encounter between a subject and the “pure emptiness or silence” of an outside, but as what Frédéric Neyrat articulates as “the encounter between silence and birdsong, lives and colors and temporalities that differentiate humans from within in order to give them other forms.”[27]

To recover this repressed history of the Hebrew as khabiru is to contribute to the urgent task of enriching and defending a political grammar of exile: tools for languages and peoples beyond the nomoi of nation-states; organs for exilic forms of life practiced by those that persist, that resist, who may call themselves Palestinian today.

Finally, the dialectics of exile calls for us to locate the desert within the city walls. From the urban maroons, who use the dense flows of urban zones as foliage, to Brecht’s figure of the crypto-emigrants who perfect the art of “erasing all traces” of their passage, let us not forget that beneath the cobblestones there is sand, and beneath the sand there are cobblestones.

[1] For my engagement with the concept of nomos, see “A Nomos of the Stateless,” Blind Field Journal, 2024.

[2] Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, Mariner Books, 2000. p.294

[3] Benedict De Spinoza, Theological-Political Treatise, edited by Jonathan Israel, Cambridge 20111. p. 214

[4] Ibid. Jaynes, p. 294.

[5] For more on Hebraic metaphysics as praxis and technology of statelessness, see Mårten Björk’s writing on the Goldberg circle in “Life Against Nature: The Goldberg Circle and the Search for a non-catastrophic Politics”, End Notes no.5

[6] Here I draw from Oliver Silverman’s recent work where he introduces the concept of a “theological ingression” between heavenly and terrestrial spheres. See: “We Are Free and We Wish to Be Free”: Political Thought and the Peasants’ War, History of the Present (2025) 15 (1): 93–115. 2025.

[7] As cited in the TPT, Deuteronomy 5.23-7 also Exodus 20.18-21

[8] Ibid, Jayne.

[9] Spinoza, ibid. 227

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid, Jayne, p.311

[13] Ibid. 311

[14] Zechariah 13, 2

[15] Ibid. 223

[16] Amnon Raz-Krakotzkin, “Exile Within Sovereignty” in The Scaffolding of Sovereignty: Global and Aesthetic Perspectives on the History of a Concept, Zvi Ben-Dor Benite, Stefanos Geroulanos, and Nicole Jerr, eds. (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017).

[17] Jean-Luc Nancy, The Inoperative Community, Minnesota Press, 1991. p.12

[18] Hannah Arendt, “The Decline of the Nation State and the End of the Rights of Man” in The Origins of Totalitarianism, Meridian, 1958.

[19] Ibid. 297

[20] Arendt insightfully distinguishes this politics of living acts from a politics of walls through the city-state and the polis: “The polis, properly speaking, is not the city-state in its physical location; it is the organization of the people as it arises of acting and speaking together, and its true space lies between people living together for this purpose, no matter where they happen to be.” The Human Condition, University of Chicago Press, 1958. p.198

[21] As stipulated in Andreas Malm’s, “In Wildness is the Liberation of the World: On Maroon Ecology and Partisan Nature”, Historial Materialism 26.3 (2018) 3–37.

[22] Malcom Ferdinand, “Behind the Colonial Silence of Wilderness”, Environmental Humanities 14:1 (march 2022)

[23] Ibid., Björk, p.311

[24] See, Karl Marx, “The Modern Theory of Colonization,” in Capital V.I, Vintage Books, 1977, p. 933.

[25] For an insightful take on the use of subjects, see, “A cautionary note on romanticizing the outsider (from Copenhagen)”, Letter #4 January 13th, 2025, Dabartis

[26] Nancy, ibid. 29, 35

[27] Frédéric Neyrat, La condition planétaire, Les Liens qui Libèrent, 2025. p.8.